Mt. Meron: What has changed since 2015?

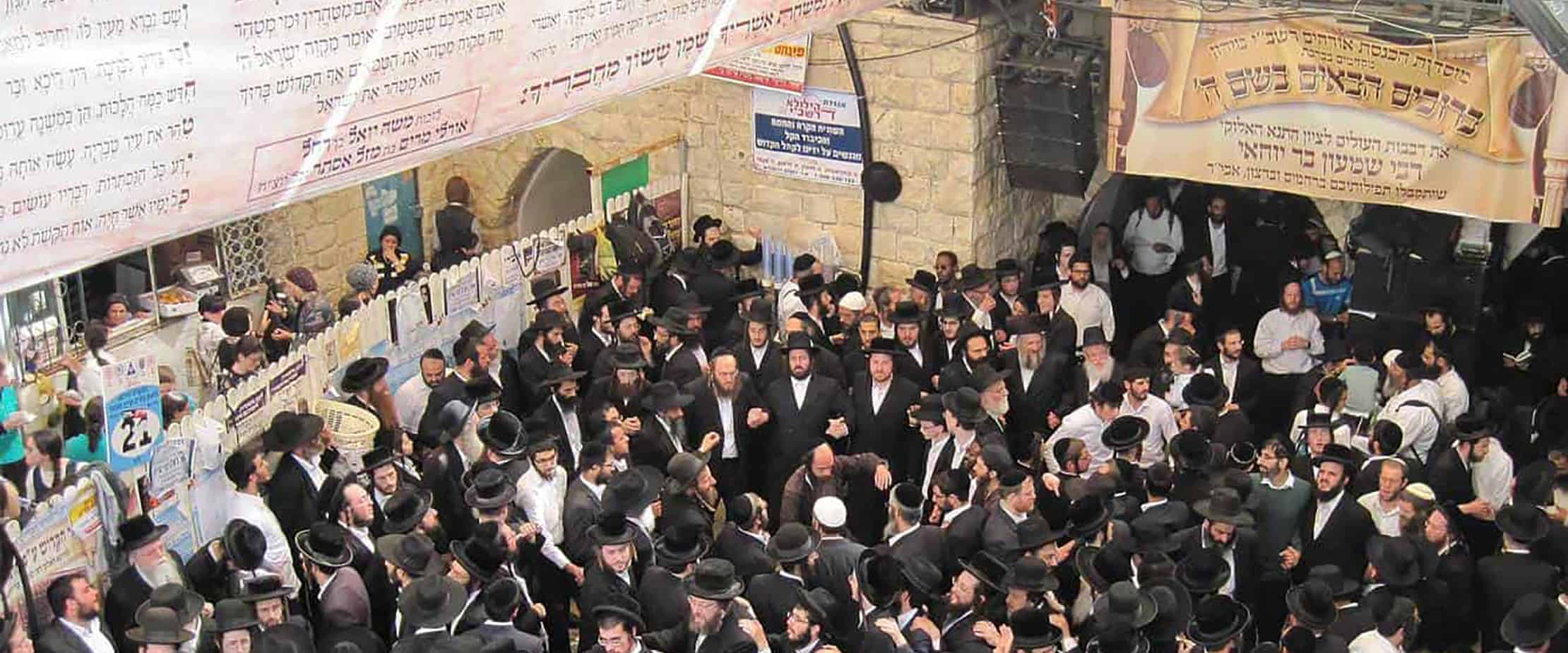

Lilach Karsenty | 20.06.2021 | Photo: Dances at Rashbi's tomb, Lag Baomer 2016, Meron, Israel

Mt. Meron was in the headlines lately because of the Lag B’Omer disaster, which raised the following questions: how much do we know about the mountain and its importance all year round for different elements of Israeli society? What have the preparations for Lag B’Omer looked like in recent years, and how were they perceived before the disaster? What is the root of the property dispute surrounding the mountain, and should Israel expropriate the land?

On July 20, 2021 the VLJI will hold an event entitled “Who's in Charge in Meron?". This is an opportunity to go back to the lectures we held in 2015, in cooperation with Daat Hamakom, at a conference called “Meron: To Whom Does It Belong?” The conflicts and concepts surrounding Mt. Meron were explored thoroughly in the lectures, at a time when the mountain was not in the headlines, and these lectures now offer an opportunity to look at the recent events with knowledge and consideration and new perspectives. You will see what questions come up after a disaster compared to questions that arise in routine, and what changes (or not) in our thinking about a certain place when the context in which it is mentioned becomes so loaded.

The first session, “Mt. Meron – Issues and Highlights,” presents the significance of Mt. Meron throughout history and describes what happens there in normal times. Prof. Elchanan Reiner discusses the designation of Mt. Meron as a sacred place as early as the fifth century, and exposes the changes that occurred in the celebrations and the pilgrim population to the mountain over the years. Prof. Doron Bar describes the Lag B’Omer celebrations in the early days of Israel, in the 1950s and 60s. Rabbi Shlomo Chelouche, director of Rashbi's (Rabbi Shimon Bar Yohai) tomb on Meron, provides a first-hand description of activity at the site on Lag B’Omer and the rest of the year, and also indicates a number of changes that occurred there over the past several decades.

The second session, “Mt. Meron, Religious Trusts, and State Authorities,” focuses on the legal aspects of sovereignty on Mt. Meron. Adv. Erez Kaminitz discusses the issue of property on Mt. Meron, explains what the religious trusts are, and argues for and against expropriating the real estate and transferring it to the state. Mr. Yosef Hirsch, from the State Comptroller's office, presents the State Comptroller reports that were issued about Mt. Meron in the years 2008, 2011 and 2014, and the changes that were and were not made in their wake. Rabbi Matityah Shrim, the head of the Sephardic trust that has been administering the site for 17 generations, describes the preparations for Lag B’Omer and the relationship with the police and other state authorities.

The third session, “The Celebration and its Arrangements,” includes two conversations with senior police officials about the annual preparation for the Lag B’Omer events. Superintendent Micha Tubul speaks about police preparation for the biggest event in the country, and crowd-control methods. Commander Ilan Mor specifies the traffic arrangements on Mt. Meron during the celebration, and discusses the challenges they present and the cooperation with the Ministry of Transportation.

In the last session, “Meron and the Tomb, Planning and Preservation,” two architects talk about planning and building at the site. Architect Eran Mebel presents the difficulties of planning at the site: from the difficulty to assess the number of visitors to the site per year, through the shortage of building permits, to the planning challenge of the Lag B’Omer festivities.

Architect Uri Miroslavski discusses the problem of adapting an ancient structure to current needs and mentions some of the unique specifications architects had to address, such as creating a separate passage for women and another passage for Cohanim. Miroslavski raises one of the essential challenges concerning Mt. Meron, through the parable of the child sticking his finger in the hole in the dike: “There is no hand, there is no stone that can stop the stream of people coming to a holy site. There is no force in the world that can do that.”

Following the parable of the finger in the dike, in conclusion, Prof. Yoram Bilu wonders whether it is even possible to reach any arrangement on Meron, and argues that on the mountain “there is clear tension between disorder and order." Bilu describes the rousing religious fervor that occurs at the site, and claims that “pilgrimages almost by definition mean disorder.” Therefore, according to Bilu, holy sites are characterized by a dialectic between order and chaos. As he wrote in an article published after the disaster in Haaretz (May 4, 2021), even the most effective operations room cannot deal with constraints stemming from the ecstatic attraction of the faithful to a holy site.”

What, then, is the relationship in a modern state between religious sanctity and secular sovereignty? What is the meaning of the resistance to Meron and to the pilgrimage to it, which came up especially after the disaster? And can we think about Israeli society without a holy site?

These questions will be raised at the seminar that will be held in July 2021 from a post-disaster perspective.

Photography: Dances at Rashbi's tomb, Lag Baomer 2016, Meron, Israel. Netanel h, Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International.