Gender gaps in politics

Hanna Herzog | 24.03.2021 | Photo: Vera Weizmann

We are facing a fourth election cycle in a row, with a gender gap in politics that is not narrowing, a gap that is consistent with the trends described in the book we published this year, “Gender Gaps in Israeli Politics", edited by Michal Shamir, Hanna Herzog, and Naomi Chazan. In this brief article Hanna Herzog portrays that gap, examined from three main aspects: one, women's representation in the parliament and government; two, differences in positions between men and women on issues on the social-political agenda; and three, voting patterns.

It is worth mentioning that until the early twentieth century women did not have the right to vote. That right was obtained after a long struggle by women the world over, including in pre-state Israel, in the years 1920-1926. Once the right to vote was gained, we saw a gradual rise in women's representation in elected institutions. In Israel women still constitute only about one third of elected officials. For the sake of political correctness, women are included on election slates, but are pushed down to unrealistic positions. Women's representation in the cabinet has slightly improved, but is far behind the dramatic changes occurring in Europe, and recently in the US, and even in non-Western countries.

It is worth mentioning that until the early twentieth century women did not have the right to vote. That right was obtained after a long struggle by women the world over, including in pre-state Israel, in the years 1920-1926. Once the right to vote was gained, we saw a gradual rise in women's representation in elected institutions. In Israel women still constitute only about one third of elected officials. For the sake of political correctness, women are included on election slates, but are pushed down to unrealistic positions. Women's representation in the cabinet has slightly improved, but is far behind the dramatic changes occurring in Europe, and recently in the US, and even in non-Western countries.

Research findings in Western democracies indicate that in the past women voted more conservative-right-wing than men, which in the literature is called the “traditional gender gap,” whereas the “modern gender gap,” that began in the 1970s, is expressed by women tending more to the left than men. A combination of factors explains these changes: women's integration in the labor market, a significant rise in women's education, and changes both in family structure and in other key social values. However, these changes are accompanied by gendered integration in public spheres. At the same time, women are also more autonomous in their political behavior and their feminist awareness is expanding.

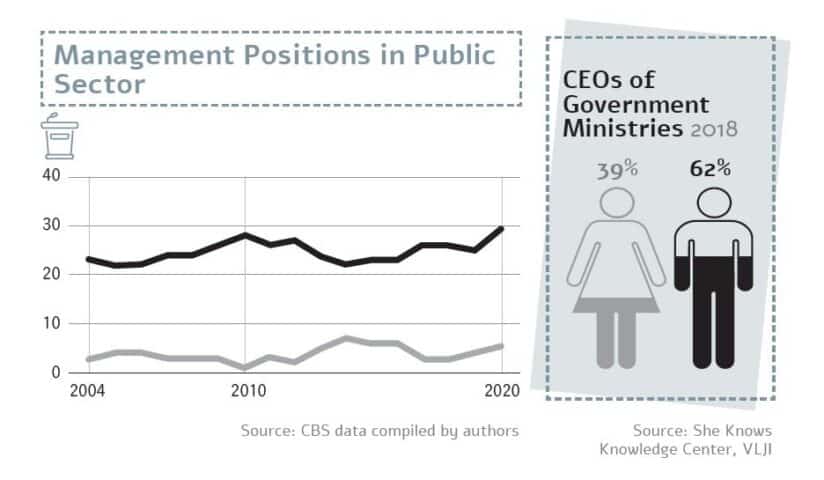

The Gender Inequality Index by the Center for the Advancement of Women in the Public Sphere (WIPS) at the VLJI indicates that the gender gap in all areas of life, except education, has not closed. All of the aforesaid explain women's greater support of the social positions of left-wing parties. Surveys in Israel indicate that on social-economic issues women's positions tend more to the left than men’s, but on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict they are located more to the right than men. The differences are not big but they are there.

A noteworthy gender gap in voting patterns occurred in the 2009 elections, when Tzipi Livni ran for prime minister. The campaign did not focus on the parties and their messages but rather on their leaders: “Tzipi or Bibi.” The Likud issued the slogan: “It's big on her.” The campaign against her questioned her leadership and suitability for the job, and was accompanied by blatant derision of her as a woman, not only by her political rivals but no less so by the media. The latter referred to her attire and hair color, compared her to a girl, and highlighted anything that conveyed the message that she is first of all a woman. The politicians asked whether she could answer the red phone if it rang in the middle of the night from Washington. Tzipi Livni did indeed receive more support from women than men, but not enough support to create significant change. The identification of the political field as a war field led by men is deeply ingrained in the dominance of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the centrality of the military as a source for the recruitment of political players.

There are still parties in Israel that exclude women, whether in their charters or their normative concepts. The High Court of Justice may have approved a compromise agreement in a petition by ten women's organizations including Nivcharot, an organization of haredi women, against Agudath Israel, and ordered to strike from the party’s charter the article preventing the election of women, but in practice the entry of women is forbidden. The processes of religification and gender separation in the public sphere are on the rise, along with the indifference, silence, and collaboration of elected public officials in the parliament and local authorities with this violation of women's rights for equality.

And finally, at the present time the Covid-19 crisis cannot be ignored. The epidemic has erected another mirror that shows us the depth of the identification of the public and political sphere with men and masculinity. In the guidelines of the government established in March 2020 it said that an emergency cabinet would be established to handle the coronavirus. It was established, but initially included no women. Likewise, in the National Security Council there were no women on the teams planning the exit strategy from the crisis. A petition to the High Court of Justice by women's organizations was needed in order to include them.

Paradoxically, the coronavirus crisis, which worsened women's condition, also created new conditions and opportunities to recognize the knowledge that was created out of women's experience, not only over years of public activity, but also during the coronavirus crisis itself. But has it been included? Do the slates competing for the fourth time in two years represent these perspectives?

In order to examine a gender gap it is not enough to count heads, but also necessary to mainstream gender and redefine the political. On this issue, as indicated by Yodaat (She Knows) – Israel Knowledge Center on Women, the gender gap is still large.

To read articles on gender: Opinion: International Women's Day, Gender Equality in Times of Coronavirus, Why do anything to prevent violence against women if you can just talk about it?

For further information on promoting gender equality, please see VLJI recorded lectures on feminism and gender.