Solidarity as an exhaustible resource

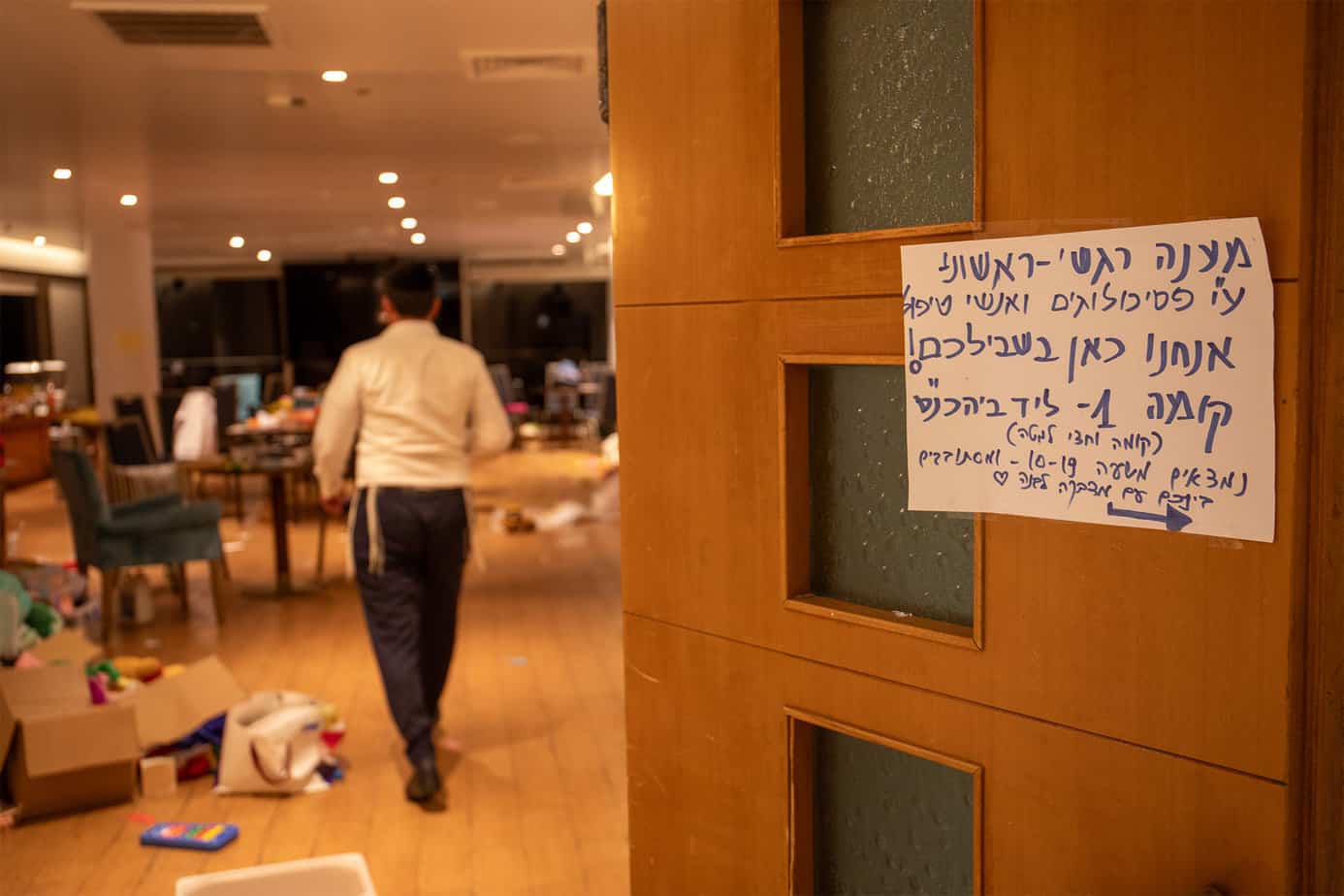

24.10.2023 | Photo: Yahel Gazit. Volunteering to pack food for One Heart

Solidarity is a confusing term. On the one hand, it seems as though one doesn’t need to explain it; when solidarity appears it is clear, externalized and public. On the other hand, solidarity raises a series of questions: Is it an emotion or an action? What is its reference group—the community? the state? the family? How is solidarity created? By acting for the benefit of another? Or perhaps the action itself is the result of a collective emotion? An attempt to answer these questions generates a much more complex picture than does the word “solidarity” as commonly used in daily life.

The meanings of solidarity in society

The concept itself was coined in the 19th century from a Latin root that refers to a certain kind of mutual responsibility of citizens. It acquired a political meaning in workers’ organization against employers, especially in matters of insurance coverage for work accidents, and Bismarck’s welfare policy in Germany in the last third of the 19th century. At the same time, solidarity as a concept became an object of interest for the social sciences.

The central question is, What binds us together? What creates a society? Is it a utilitarian, clear and calculated commonality of interests between individuals or, as the sociologist Emile Durkheim suggested, a collective sense of belonging that draws the social circle? Durkheim called that feeling “pre-contractual solidarity” and actually argued that before individuals sign contracts between them and create rules and regulations of social behavior they must recognize each other as belonging to the same collective. He called that act of identification solidarity.

It is no wonder that the concept is developing in a modern, individualistic and materialistic society. Some argue that solidarity is the glue binding individuals who constitute a certain collective, a glue that in normal times is invisible but in times of crisis may be the most salient social phenomenon. Solidarity is a powerful social engine. In the name of solidarity individuals are willing to pay a high price and sacrifice much of their time, energy, money, ability and body.

In its institutional manifestation, solidarity appears, for example, in laws and arrangements that create general mutual responsibility, including payment of taxes, health insurance, education and military service. In its informal manifestation, namely not by virtue of an order or law, solidarity appears in its full force as an expression of actions aimed primarily at the public good. Which public? One to which the person performing the act of solidarity considers himself or herself as belonging: the national group, the ethnic group, humanity, or any other identity group.

Why is trust important for maintaining solidarity?

Solidarity is very powerful. At its peak it has the power to change social, political and economic orders that in normal times would change much more slowly. Its power increases particularly in times of crisis, and the extent of sacrifice it can then elicit from the public is greater than in normal times. But what is the extent of that collective sacrifice in terms of time and social space? In other words, for how long can one demand—in the name of solidarity—the same degree of sacrifice? What are the limits of sacrifice, who does it include and who does it exclude? How rigid are the boundaries of solidarity between “us” and “them”?

One way to answer these questions is to consider the concept of trust. Solidarity creates trust between parts of society that may have been suspicious of, or even antagonistic to, each other previously, and in that sense it often has a positive effect in creating the social glue of cohesion. But trust is also an important element in maintaining solidarity—trust that the sacrifice is largely equal and transparent and that it does not involve interests beyond participation in solidary action for the common good.

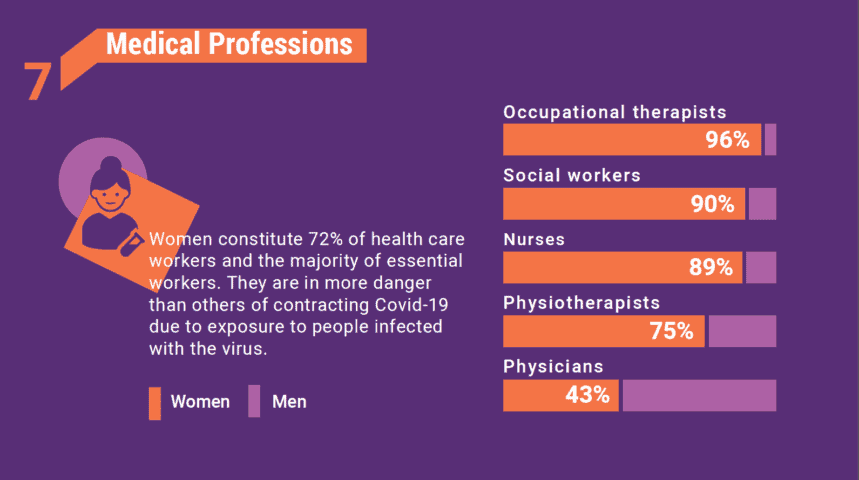

Think, for example, about the first wave of the COVID-19 epidemic, when there was no vaccine and the only possible coping method was lockdown. The sacrifice that was required was tremendous, and the restrictions on gatherings were extremely severe. But the Israeli public adhered to them at the beginning. A sense of solidarity, that we are all in this difficult situation together, created the willingness to make the sacrifice that stemmed mainly from trust. But that trust was broken the moment it turned out that the sacrifice was not equal: It turned out that the president, the prime minister, the Knesset speaker and other public figures violated the decrees and held Passover Seders in the physical presence of their family members, and schools did not close down for all parts of the population. Once that trust was breached and began to be undermined, solidarity itself crumbled, to the point that certain populations began to express mistrust and complete suspicion of the decision makers.

The linkage between trust and solidarity is therefore central. Solidarity is built of trust and in turn creates it. Here, too, we need to look at the “sociologization of trust”: Trust is distributed differentially among different social groups. Today, during these horrific times of the October 2023 war, it seems that the public does not give its trust to the experts or the political leadership but rather aims more horizontally at an Israeli “togetherness,” which, it should be noted, is mainly Jewish. Even that horizontal trust is fragile and has a high potential of dissipating. Once it is cracked and torn and the public is ripped back into camps and factions, solidarity, too, as a powerful resource will vanish.

Perhaps it can be formulated as an economic law: For solidarity to persist, the level of identification and trust between members of the community has to be greater than the price they perceive of their own sacrifice. Once that level drops, the price of sacrifice rises and people are less willing to pay it. What is the dynamic that leads to this? The answer requires an empirical analysis of specific cases, but the rule is clear: Solidarity is an exhaustible resource.

Reading recommendations: the essay A model of solidarity; the project Does solidarity contribute to health?